10 July 2024

Coca – much more than a drug source

We look at the complex story behind one of the most infamous plants, and the science leading us to better understand it

For thousands of years, Indigenous communities of South America have used the coca plant as a medicine, a tea ingredient and a nutritional supplement, with the plant being woven into religion and spirituality.

Even one of the world’s most popular drinks owes half its name to coca, alongside another plant used in its original recipe: kola. Yet what coca is also well-known as the source of the narcotic drug, cocaine.

An 8000-year history of traditional coca use by humans is now overshadowed by barely a century of drug-trade-driven, industrialised coca production that has put the plant at the heart of deforestation and armed conflict.

This presents a huge challenge for governments and communities alike. How do you regulate the alternative usage and production of this plant without depriving Andean and Amazonian communities of their fair, historic usage? Can botanists help tell the difference between wild and cultivated coca varieties? What types of scientific data are best for this and also most practical in the field?

New research led by Kew scientists Natalia Przelomska, Oscar Alejandro Pérez-Escobar, and Alexandre Antonelli has started to answer these questions as we work to understand coca’s complex tale.

What is coca?

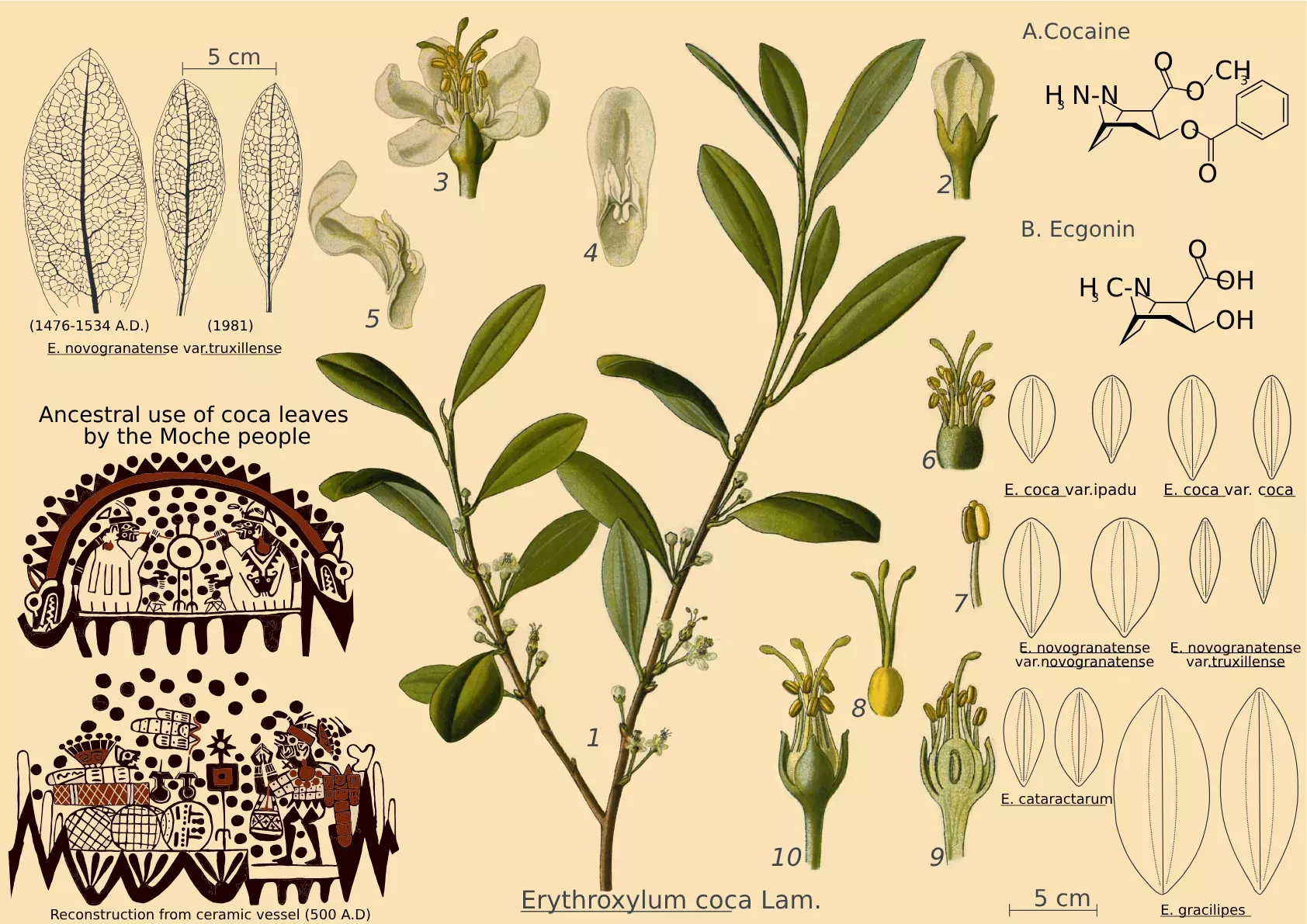

Coca plants belong to a group of 270 species of the genus Erythroxylum. Just two of these tropical plants are cultivated by people at scale: E. novogranatense in the drier regions and E. coca in humid forest areas of the South American continent.

Coca grows as a small, bushy plant, with tiny flowers and bright red fruits sprouting in groups along the length of its long thin branches. Just like any other plant, the species serves a role in its native ecosystems as a food source and home for numerous other species. It is the leaves that are of interest to many people though. Each contains many powerful plant compounds that can be used as medicine or stimulants, amongst these is cocaine.

Leaves were traditionally chewed to gain the benefits from all the compounds in a measured dose, but today cocaine can be extracted at scale. This practice has detrimental impacts on the environment, requiring thousands of leaves and the application of harmful chemicals.

Bodies including the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) have already worked for years towards understanding and tackling the illegal trade of cocaine, just as governments have attempted to dampen production by destroying unlawful coca plantations. The UNODC is monitoring the expanding and contracting of coca plantations year on year, shaping valuable information that could be vastly enhanced if combined with the knowledge of which plants are being grown. Until now, efforts have been hampered by the total lack of reliable identification.

It is notoriously difficult to distinguish between the varieties of crop coca, or even tell the difference between cultivated coca and some of the wild coca species.

The problems of using leaf size

From the late 1970s, rough guidelines were created to distinguish between coca species and crop varieties based on the shape and size of their leaves, with few other distinguishing features to go on.

Specifically, the leaves of farmed coca varieties were thought to have become smaller, rounder and softer than those of their wild relatives. This is referred to as the ‘domestication syndrome’ of coca, and is a result of a plant’s appearance being shaped by adaptation to their new human-dominated existence. We see the same phenomenon in other domesticated crops like grains and fruits that have changed to become more human-palatable and easier to harvest.

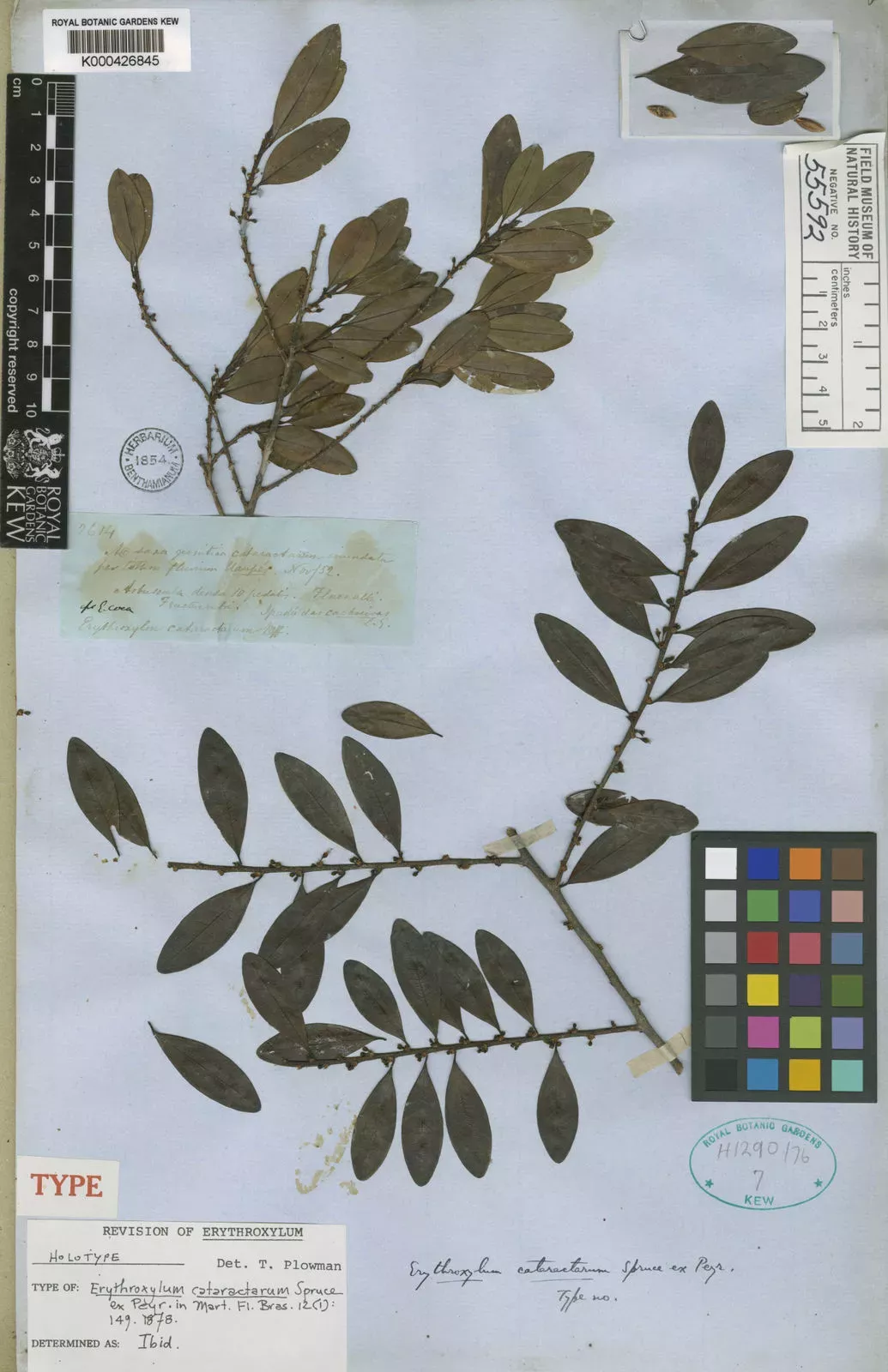

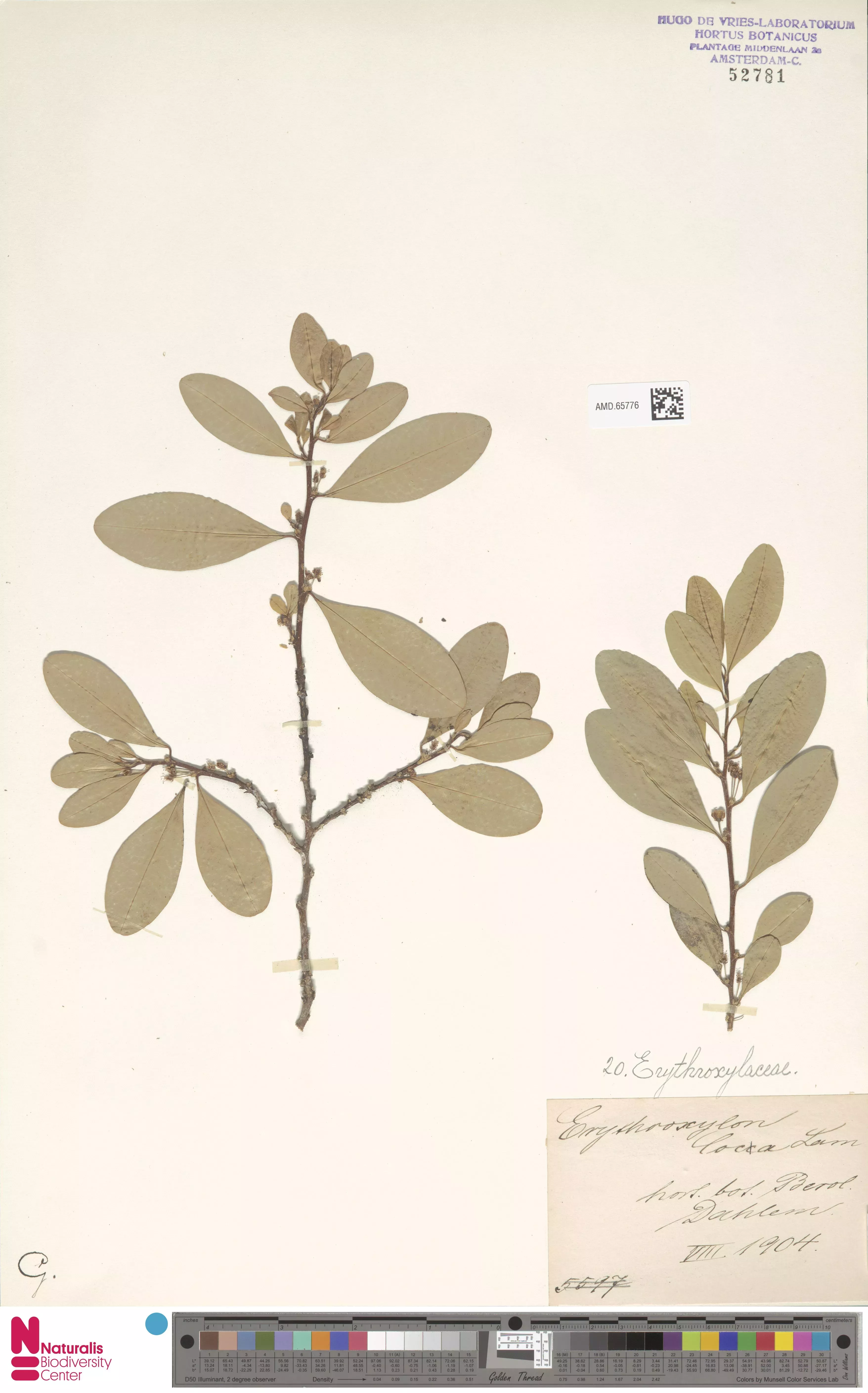

The researchers put this old method of coca identification to the test with some of the world’s largest dried plant collections – including the RBG Kew Herbarium. The method: Take 1,163 leaf outlines from 342 digital herbarium specimens of wild and cultivated coca, measure them in detail and apply statistical methods to seek a clear answer. This first stage of the work was devised and carried out by Rudy Diaz, Master’s student at RBG Kew and Queen Mary, University of London.

The result: a huge amount of overlap in leaf shape and size between coca types. The domestication syndrome trend may be there, but not consistently enough to be used for identification.. It’s extremely likely that coca varieties are being misidentified in plantations.

With no reliable way of telling the difference between coca grown for traditional purposes, coca grown for commercial cocaine production and coca growing wild naturally, the current methods of identification are out-of-date.

We need to look beyond coca’s physical appearance to what lies within.

Can DNA bring balance to coca use?

The modern field of DNA research has grown hand in hand with the traditional techniques pioneered by the first taxonomists. A combined approach has revolutionised our ability to understand the relationships between species.

Our scientists took the DNA from 18 Erythroxylum plant specimens from the Kew Herbarium to interrogate the relationships previously predicted from appearance alone. This information builds on the limited genetic datasets that have only just started to shed light on wild-cultivated coca plant relationships.

We’re now able to look back into the past to the origins of modern coca varieties by constructing an evolutionary tree. It’s likely that the two species that have become today’s domestic coca varieties began their split from each other more than 400,000 years before any humans arrived on the American continent.

Interestingly, what we see at the DNA level is only slight differences between wild species and some cultivated varieties – though others are highly distinct. We also see the continued exchange of DNA between them.

Imagine the knowledge we might gain by building a full evolutionary tree of every coca variety, and studying in detail the genomes of the species used by people today. How easy it would become to spot and monitor new coca types (such as hybrid varieties grown for increased resilience and cocaine yield) as they emerge.

The future of coca – tradition, conservation, policy

Attitudes are changing out there. International governments are seeking to find balanced approaches to the management of coca within and between their borders. Modern integrative taxonomy has the potential to provide the answers that decision-makers need to make real change.

By building a full coca family tree and discerning properly how we can identify today’s and tomorrow’s coca varieties, we empower local authorities and organisations by helping them to understand coca’s diversity On one side this may mean more effective action against illegal activity, but, crucially, it also gives more evidence to support conservation of immensely valuable wild coca biodiversity and the species on which thousands of years of community heritage have been built.

This paper is the first result on a long journey of Kew’s research on coca. Stay tuned as progress continues.