25 March 2024

Uncovering our oldest specimen and the poisonous scandal behind its collector

Just how old is our oldest herbarium specimen, and who was the colourful character who collected it?

.png9e15.webp)

Our Herbarium at Kew was founded more than 170 years ago, but the oldest specimens in the collection go back much further. They reveal the determined efforts of early botanists to catalogue the natural world, both at home and abroad.

The sense of history inside our Herbarium is palpable. Three-storey spiral staircases and cast-iron walkways in the grand Victorian wing lead to towering wooden cupboards stuffed with bundles of dried plants from all over the world, each carefully mounted on a sheet of paper.

Inside Kew’s Herbarium

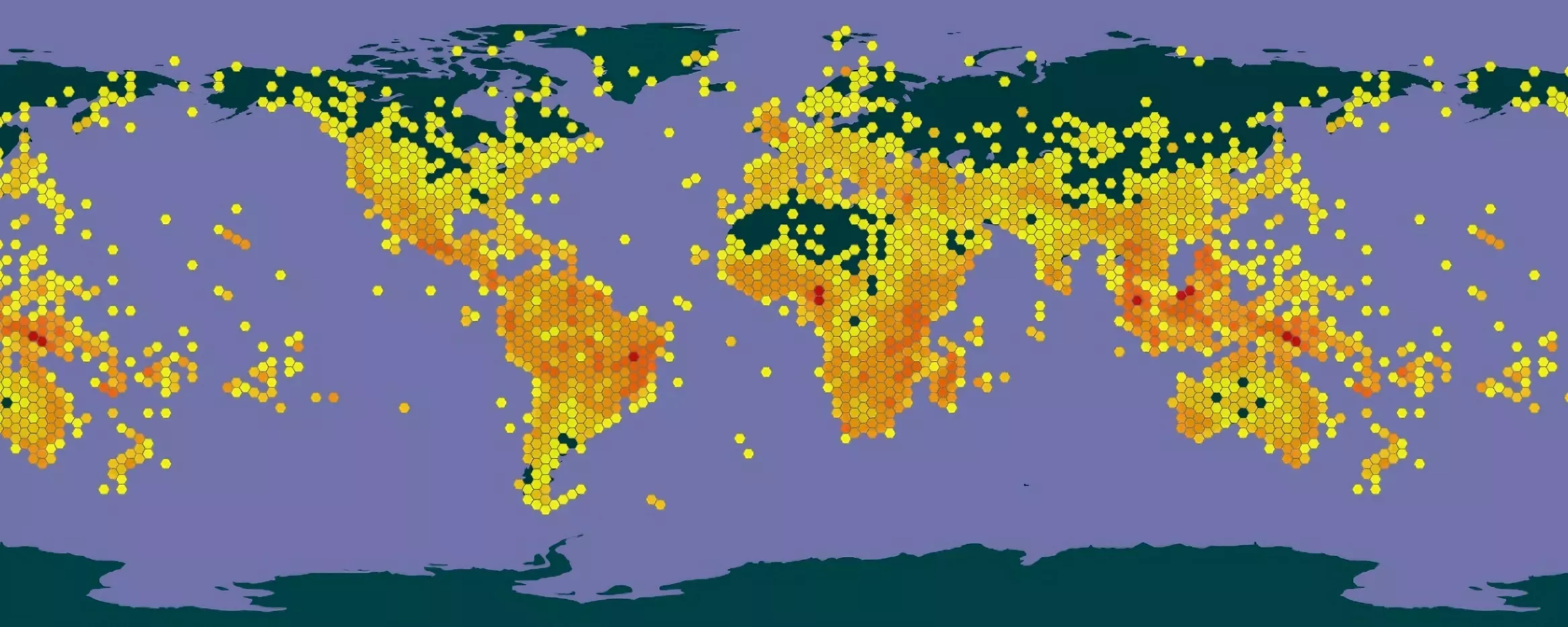

With around seven million existing specimens (which we are currently digitising) and some 20,000 - 25,000 additions every year, our collection is one of the largest in the world and an invaluable source of information on everything from tropical orchids to Arctic-alpine plants growing in the coldest climates.

The Herbarium, however, is not only remarkable for its geographic spread. It is also a time capsule. Its deep historical roots allow scientists to travel back in time to see where plants grew in the past, providing crucial insights into how the distribution of species has changed over the years.

Kew’s oldest pressed plants far predate the building in which they are housed, since they include specimens acquired from other, older herbaria. These centuries-old specimens tell fascinating stories about the men and women whose passion for botany turbo-charged scientific understanding during the Age of Enlightenment (roughly 1685 - 1815).

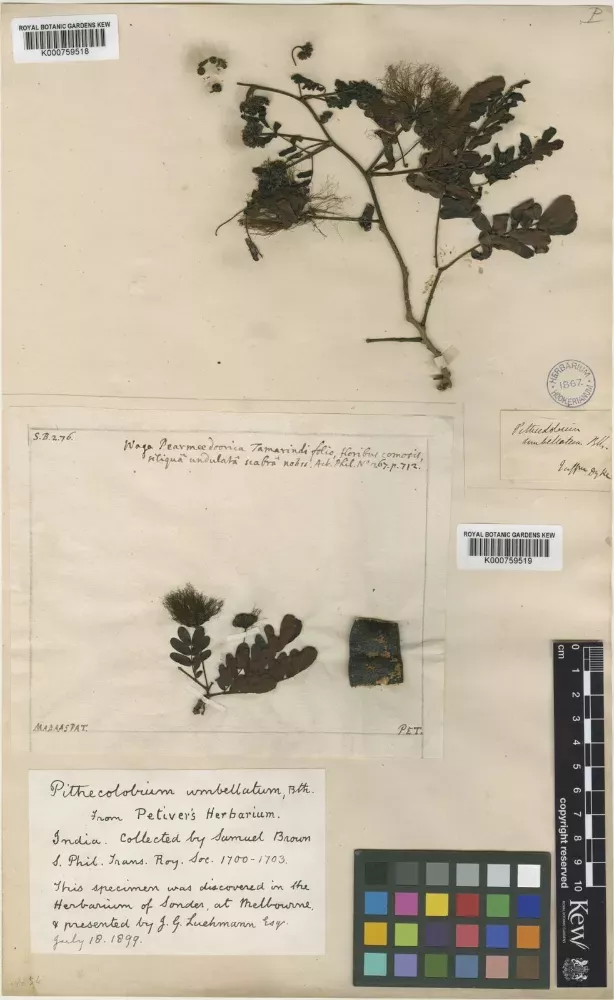

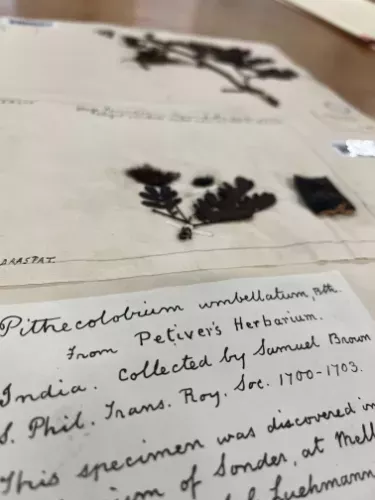

The man behind our oldest specimen

They include colourful characters like Samuel Browne, a surgeon working for the East India Company (EIC) at the end of the 17th century, whose specimens from the pea family collected in 1696 from around Madras – now Chennai – are the oldest in our Herbarium.

.jpg5aaa.webp)

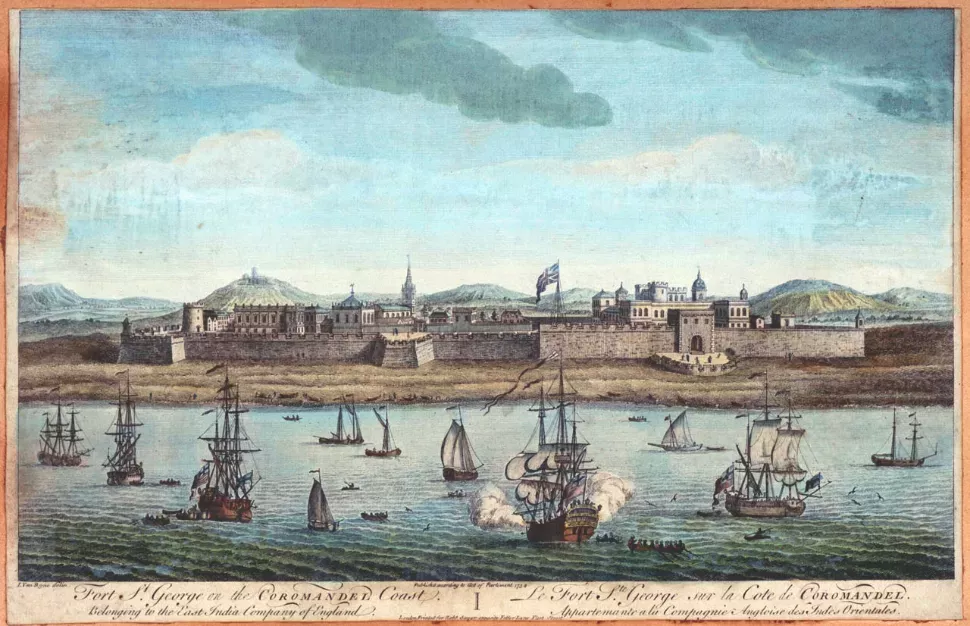

Browne, whose name was also spelt ‘Brown’, was appointed surgeon in the Military Hospital at Fort St George, Madras, in 1688. At the time, Madras was a critical centre of commerce and a fast-growing settlement, being the first English colonial town in India.

Browne’s collection grows

In addition to his duties as a surgeon, Browne was commissioned to collect plants that could be useful as medicines or for other purposes.

He was an enthusiastic collector and shipped well-prepared herbarium sheets to London, along with some seeds that were planted in the Apothecaries’ Garden in London, now known as Chelsea Physic Garden.

Browne also collaborated with Tamil and Telegu speakers on the ground in India, allowing him to give the local names of plants he found and say how they were used by people living in the area.

He had an extended correspondence with James Petiver, a keen collector in London, who ran an apothecary shop and belonged to the Temple Coffee House Botany Club, which met near Fleet Street and was arguably the first natural history society in Britain.

Together, Browne and Petiver published a series of articles in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society between 1698 and 1703, containing accounts of the plants collected by Browne in India.

Most of Browne’s plant material is now in London’s Natural History Museum because Petiver’s collections, including the Madras specimens, eventually ended up in the herbarium of Hans Sloane, another member of the coffee-drinking botany club.

Kew’s specimens are ‘duplicates’, or extra samples of the same species collected in the field by Browne.

Scandal overshadows Browne’s career in medicine

Unfortunately, Browne’s medical career did not proceed as smoothly as his botanical one. In 1693, he was at the centre of a poisoning scandal when James Wheeler, a member of the governing council of Fort St George, died after treatment under his care.

Wheeler fell ill having been given medication ground in the same mortar in which arsenic had been prepared for another patient. Even though the medicine had been compounded by his assistant, Browne confessed to murder and went on trial, but was acquitted.

His troubles did not stop there. In 1695, he was arrested for drunkenly challenging another former EIC surgeon to duel and two years later he was fined for robbing and attacking a Mughal customs official.

Beyond Browne – other early herbarium specimens

Browne died in 1698 – but the EIC continued to play an important role in the arrival of plant specimens at Kew. Another very early specimen in the Herbarium is of Indigofera astragalina, collected by Daniel du Bois at Fort St George in 1700.

%20(1).jpgc600.webp)

_in_hyderabad%2c_ap_w_img_0202%20(3)%20(1).jpg1b19.webp)

Known as silky indigo, it belongs to the same genus as Indigofera tinctoria, the plant that was used widely in factories in India for the production of blue indigo dye.

By the 18th century, the surge in interest in the natural world had reached right across educated society – as highlighted by another of Kew’s venerable plant collectors, the Reverend John Lightfoot.

Lightfoot was a keen botanist and conchologist – a collector of mollusc shells – who used his spare time for field study and research. He was a friend of Gilbert White, the famous parson-naturalist who went on to influence Charles Darwin, and both men exemplify the major contribution of the English clergy to natural history at the time.

Lightfoot’s specimens fit for a Queen

Lightfoot was helped in his endeavours by the Dowager Duchess of Portland, who appointed him as chaplain in 1767, when he was 31.

She was a leading patron of the natural sciences, with an extensive natural history collection of her own, and she hosted leading scientific figures at her grand house in Buckinghamshire, including Sir Joseph Banks, who became Kew's first unofficial director on his return from the travelling the South Seas with Captain Cook.

.jpga06c.webp)

From about 1770 until his death in 1788, Lightfoot collected a wide range of plants by travelling across the British Isles, creating a fine herbarium in the process. After his death, his herbarium was bought by none other than King George III for 100 guineas as a gift for his wife Queen Charlotte, who was a big fan of botany.

Today, Lightfoot’s specimens are kept within our herbarium but, as a ‘special’ collection, they are stored separately from the rest of our specimens.

A note on Kew in the age of empire

During the 18th and 19th centuries, Kew was actively engaged in global plant exchange, resulting in a complex entanglement with the history of empire.

Led by the intense competition to find, identify and name species new to the west, Kew’s director William Hooker (1785–1865) sent plant collectors around the world to gather specimens and seeds to add to Kew’s collections, often benefiting from local knowledge. As more material was gathered, Kew’s collection diversified, resulting in the Collections we now have within our herbarium.

Today, Kew is on a journey of reflection, re-evaluating our history, scientific practices, policies and connections to empire and colonial history.

Old specimens, future solutions

Over the last 300 years, Kew’s collection has grown hugely, with notable contributions from the likes of Darwin and David Livingstone. But despite all this history, the Herbarium is not a museum – it is a working collection and a centre of live scientific research.

The need for detailed insights into the world of botany has never been greater as humanity confronts the dangers of a rapidly warming planet and biodiversity loss, with two in five plant species estimated to be under threat.

Scientific analysis of botanical collections can not only help predict responses to climate change but also identify biological molecules that may be useful as new medicines or nutrients.

And there is an urgent need to make all this information available to researchers who need it, which is why our project to digitise our entire collection is so important.

At an estimated cost of £29m, our digitisation programme is the largest project in Kew’s history and work is now well underway to produce high-resolution images and key label data for all 7 million specimens in the Herbarium, plus another 1.25 million fungal specimens.

We’re on track to complete the project by 2026, making our entire digitised collections available to anyone anywhere in the world for free - accelerating science to find solutions for our greatest global challenges.

Help us digitise our prestigious collections

Get involved with these new opportunities

%20(1).jpgcea8.webp)

Volunteer

Become part of Kew's ambitious project and help make one of the largest collections in the world freely accessible to everyone around the world.

%20(1).jpg5405.webp)

Donate

Donate today and immortalise a piece of botanic history that can aid research into urgent global challenges - helping protect our planet for future generations.

%20(1).jpg1da2.webp)

Join

See what job opportunities are available to digitise our collection and play a part in helping scientists across the world access our invaluable specimens.

.png2082.webp)