1 August 2024

Five medicinal plants that changed the game

Meet some of the plants that gave us a medical step forward.

Throughout history, humans have been making use of plants for their medicinal properties. And there’s no sign of us slowing down.

It was only a few years ago that scientists isolated an anti-cancer medication called Kadcyla from an African plant in the genus Maytenus.

Along with fungi, plants are a critical resource in discovering new medications. As we celebrate Marc Quinn: Light into Life, which features sculptures of medicinal plants, meet some of the plants that have given us crucial medicines.

Pacific yew (Taxus brevifolia)

In the latter half of the 20th century, a small yew tree growing in the forests of the Pacific Northwest became the next big thing in cancer treatments.

Paclitaxel, also known as taxol, was discovered in pacific yew tree bark, and was shown to be an effective treatment against a number of cancers.

Unfortunately, the pacific yew was already under threat from logging, putting a potential transformative medicine at risk. Fortunately, in the mid-1990s, scientists were able to synthesise paclitaxel from a more readily available natural precursor in the lab, sparing the tree from overharvesting.

Today, paclitaxel can be synthesised from the bark of European yews (Taxus baccata), a wide-spread species that can be sustainably harvested at no risk of extinction.

Snowdrops (Galanthus nivalis) and daffodils (Narcissus)

Common snowdrops are among the first spring blooms that decorate woodland floors, meadows, and gardens with a carpet of white.

But did you know snowdrops also contain a substance that can help treat dementia?

Snowdrops contain a compound called galantamine which is used in modern Alzheimer’s medicines and is also used to relieve traumatic injuries to the nervous system.

Galantamine is also found in the bulbs of daffodils and other members of the Amaryllidaceae family. In 2022, a farmer in Wales found that daffodils grown under stress in heavy wind conditions produced more galantamine, which could help increase production of game-changing treatments.

Snowdrops and daffodils are both common sights across Kew during the spring months, especially in the Alpine Garden.

Madagascar periwinkle (Catharanthus roseus)

Originally only found on the eponymous island, the Madagascar periwinkle is now widely cultivated around the world, as it is vital in the production of anti-cancer medications.

Like many plants used for medicines, all parts of the Madagascar periwinkle are toxic if eaten. The medicinal compounds that can fight cancer must first be isolated in safe doses before being used in treatments.

The periwinkle naturally only produces these compounds in small doses, meaning that cultivation is a costly process. As a result, scientists are trying to understand more about how these compounds are made, and how we might boost it.

Despite many of Madagascar’s native species being under threat from human activity, the periwinkle has continued to thrive, thanks to its affinity for growing in disturbed areas.

See the Madagascar periwinkle in Kew’s Palm House on your next visit.

Naked ladies (Colchicum autumnale)

Despite being toxic to the touch, naked ladies are used medicinally around the world as a source of a chemical called colchicine.

This chemical works as an anti-inflammatory, reducing swelling, and is used to treat gout when other medicines are not suitable. Colchicine is found in the corm, an underground stem that looks similar to a plant bulb.

Along with its medical use, colchicine is also popular amongst horticulturalists, as it can be used in plant breeding to create larger and faster growing plants.

Naked ladies get their slightly risqué common name due to the flowers appearing before the leaves, giving them a ‘naked’ appearance.

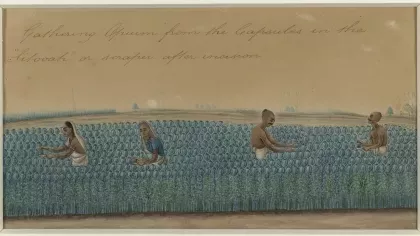

Opium poppy (Papaver somniferum)

The bright flowers of the opium poppy are beautiful, but behind the petals lies a medication that has been both a blessing and a curse.

Opium is collected from the poppy by scratching the seed pods of the plant, then collecting the white latex that is produced. This substance has been used as a medicine and recreational drug for thousands of years, becoming enormously profitable in the 17th century, resulting in several wars over its sale.

The specific name of the poppy, somniferum, is a hint towards the pain relief that opium can provide, as it refers to its sedative qualities, literally meaning ‘sleep-bringing’.

Today, opium poppies are still used in the production of opioid pain medications, including morphine and codeine. It is also the source of the drug heroin. Opioids are dangerously addictive, and while useful in pain management, need to be carefully used.

While probably most famous for being the source of the eponymous drug, the opium poppy is also cultivated for its tasty seeds, along with being popular as an ornamental plant.

These five examples are just scratching the surface when it comes to the hundreds of species that we've utilised for medicines. And that's not even mentioning how crucial treatments have come from fungi species. That's why it's so crucial we understand what's out there.

In Kew's State of the World’s Plants and Fungi 2023, we revealed that scientists predict that three out of every four unknown plant species are under threat. On top of this, only 0.4% of known fungi species have been assessed for their IUCN Red List conservation status. We're at risk of losing these species before we even identify them, meaning potential world-changing medicines are disappearing forever.

That's why Kew's work is more vital than ever. We're working to identify more plants and fungi, and understand how we can protect them from extinction, and through doing so, safeguard future medical breakthroughs.

.jpgb9c6.webp)