24 April 2024

Tales across time from the Plant Tree of Life

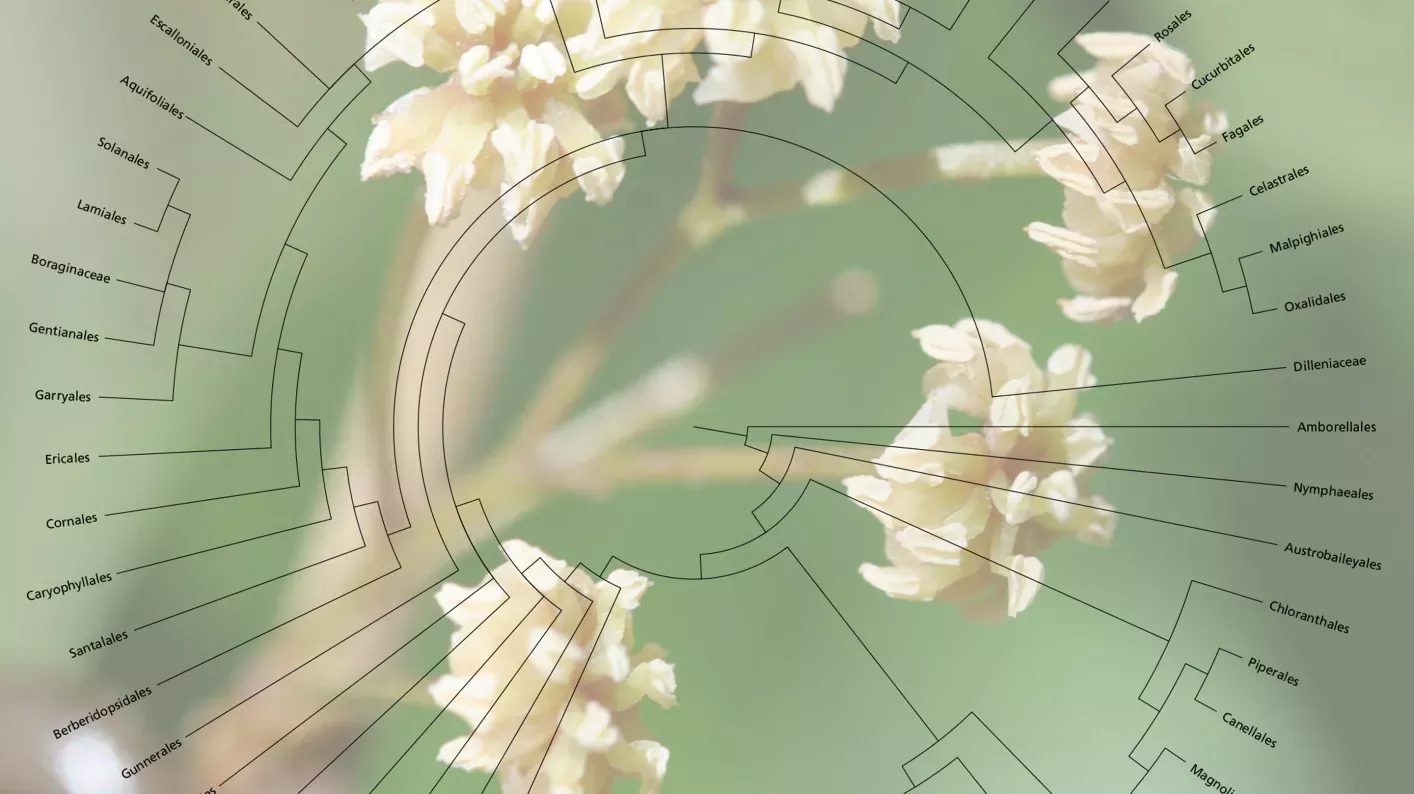

An ever-growing plant tree of life is the key to answering questions from 200 years ago and those of tomorrow

Flowering plants are found across every corner of the Earth – from the steamiest tropics to the rocky outcrops of the Antarctic.

Their astonishing diversity, their ability to adapt and survive in the face of environmental change, and their usefulness to humans have made them a subject of study for thousands of years already.

A modern revolution in the study of DNA has allowed us to understand the evolution of this complex kingdom of life in more detail than ever before. Here we share the latest achievement: 1.8 billion letters of the DNA code sequenced from more than 9500 plant species, made available to use by anyone, anywhere, for free!

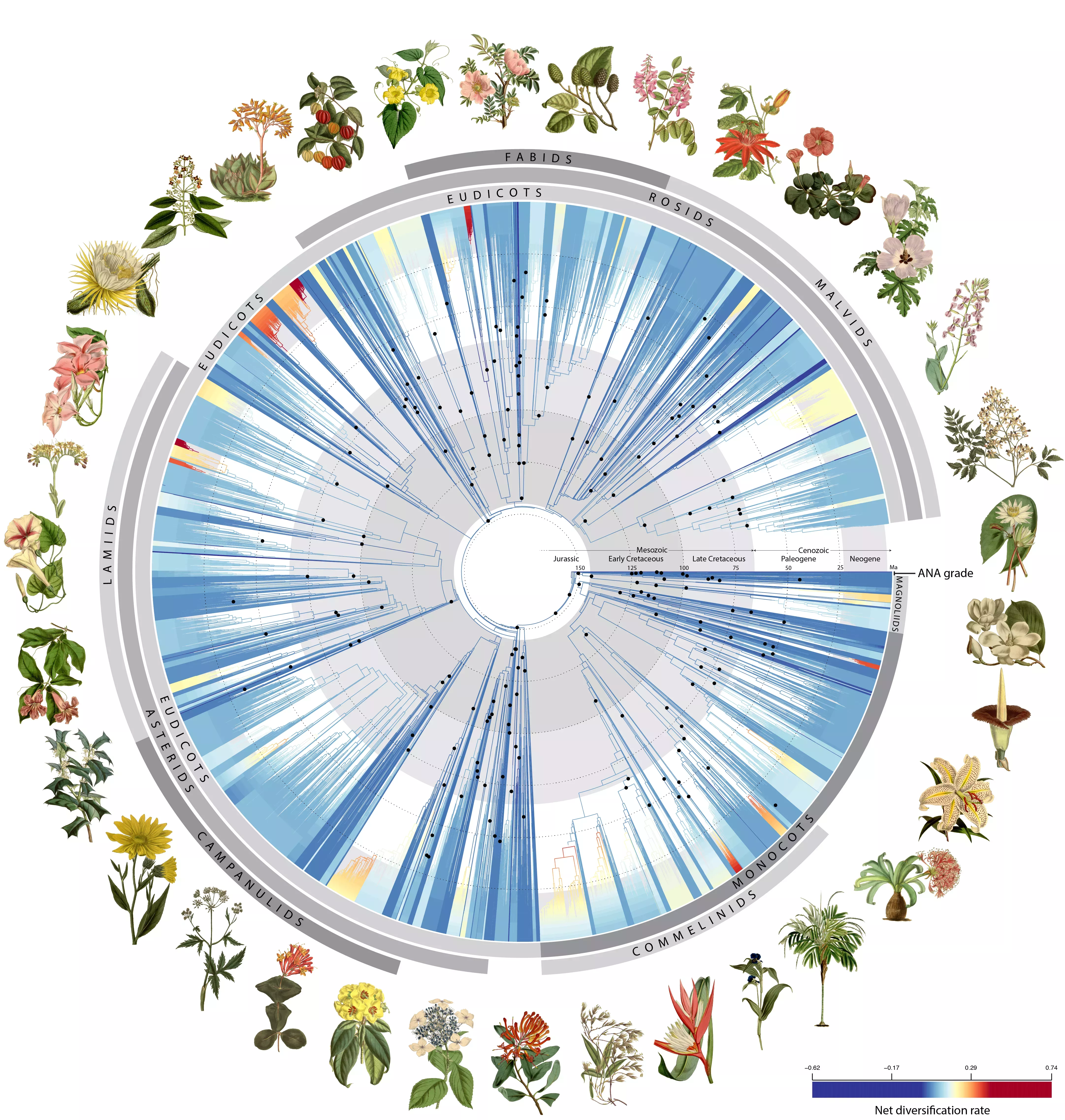

This huge piece of work published in Nature and forming part of Kew’s Tree of Life Initiative has brought together 279 scientists from 138 institutions and 27 countries under one cause – to sequence the DNA of as many flowering plants as possible and build a definitive plant tree of life stretching back to their origin.

The tree of life unlocks answers to questions posed centuries ago by early scientists including Darwin himself. It also helps us to solve puzzles and find solutions that will shape our planet in the years ahead.

Time travel partnership with 19th century scientists

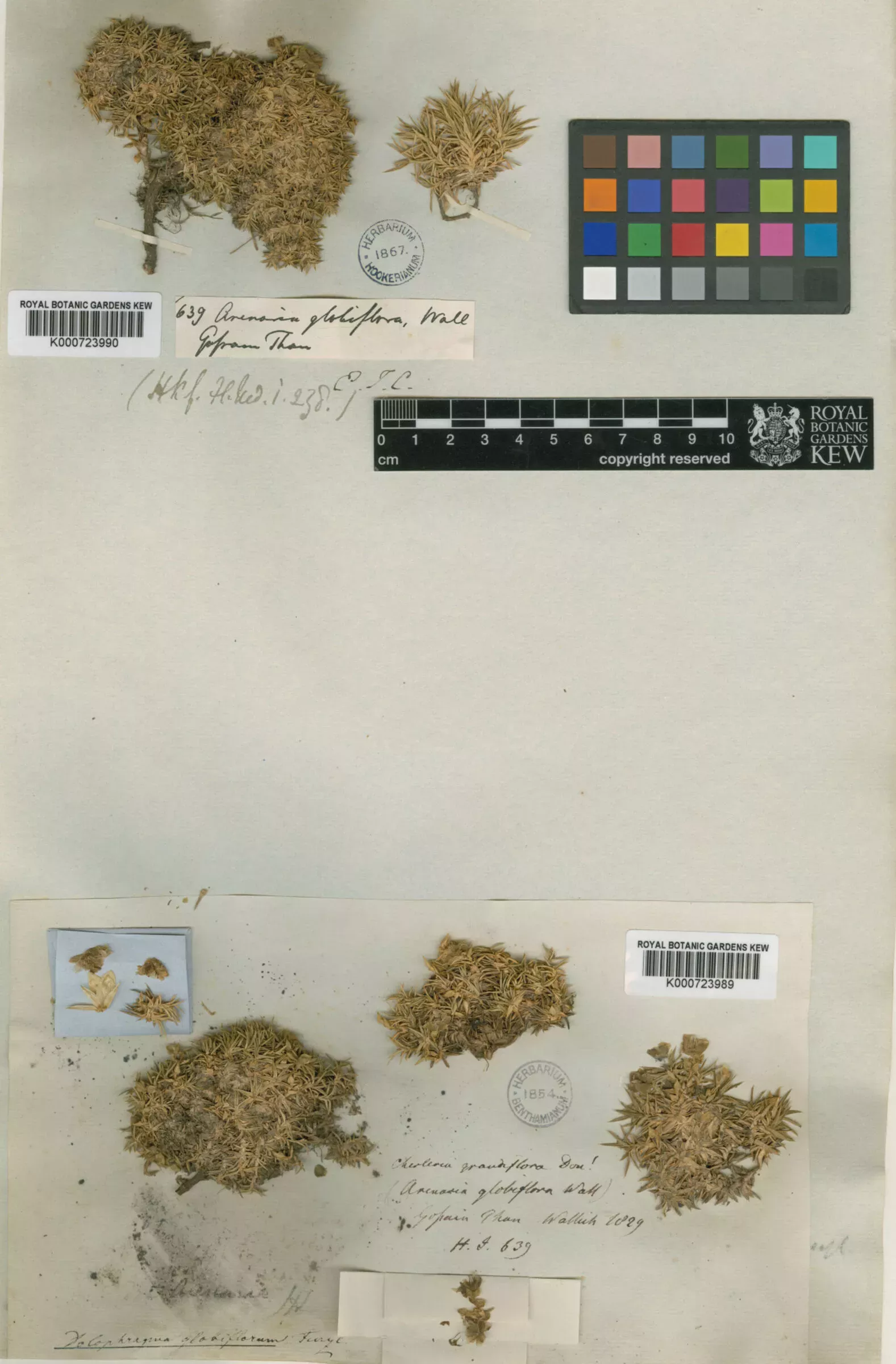

Advances in our ability to study ancient DNA has turned our collection of >8 million dried plant and fungal specimens into a remarkable time capsule.

The sandwort (Arenaria globiflora) specimen pictured below was collected almost 200 years ago in Nepal, and yet it has been possible to extract enough DNA to confidently place this species within the tree of life.

These early collectors had not even heard of DNA and could not have imagined the future use of their specimens. In a sense we are collaborating with botanists of the past to answer questions that they could scarcely have formulated.

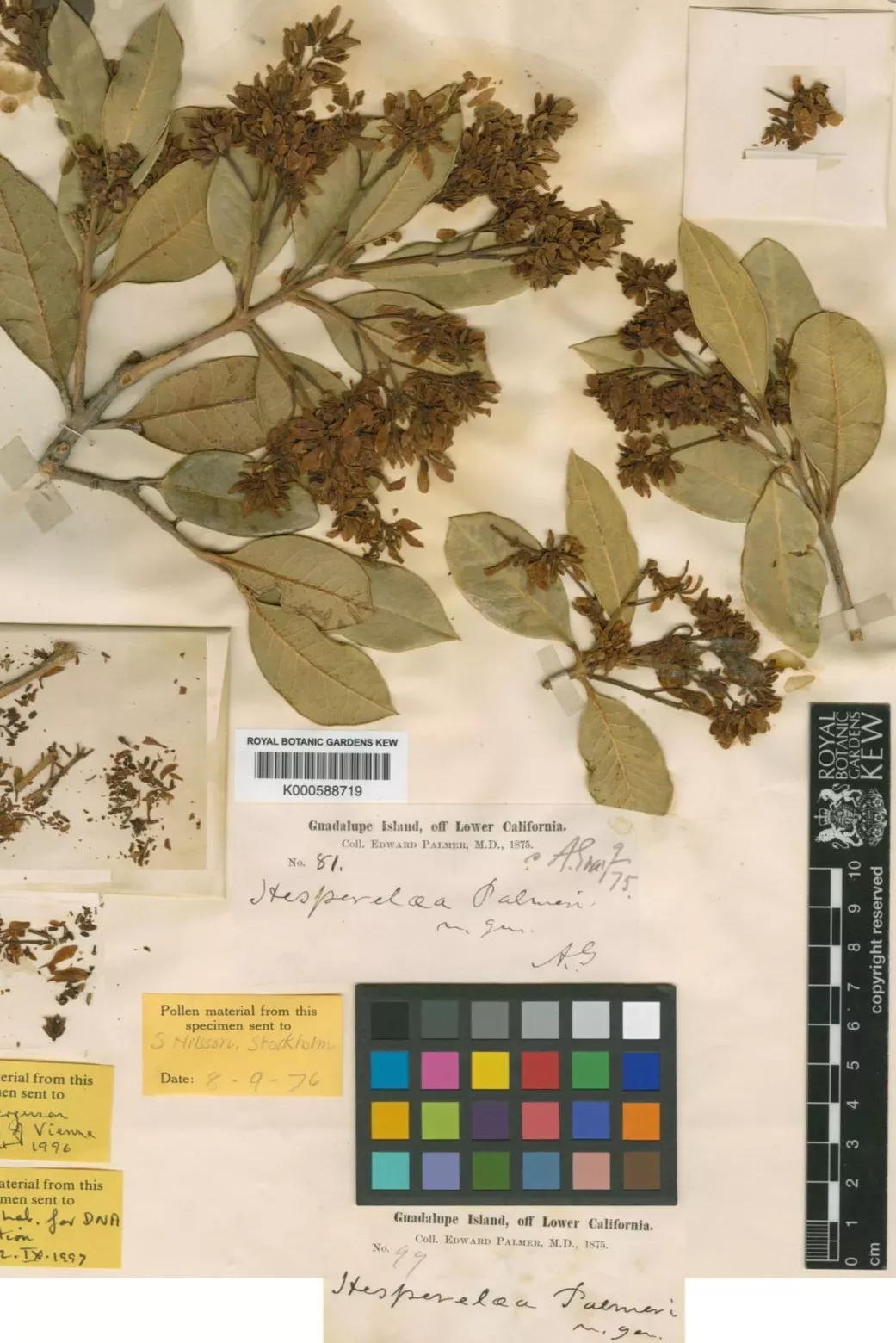

This collaboration across time is even allowing us to learn about species that are already extinct and lost to us. For example, DNA extractions from a herbarium specimen of the extinct Guadalupe Island olive (Hesperelaea palmeri) have enabled us to shed light on the species’ evolutionary history, even though no living plant has been seen since 1875.

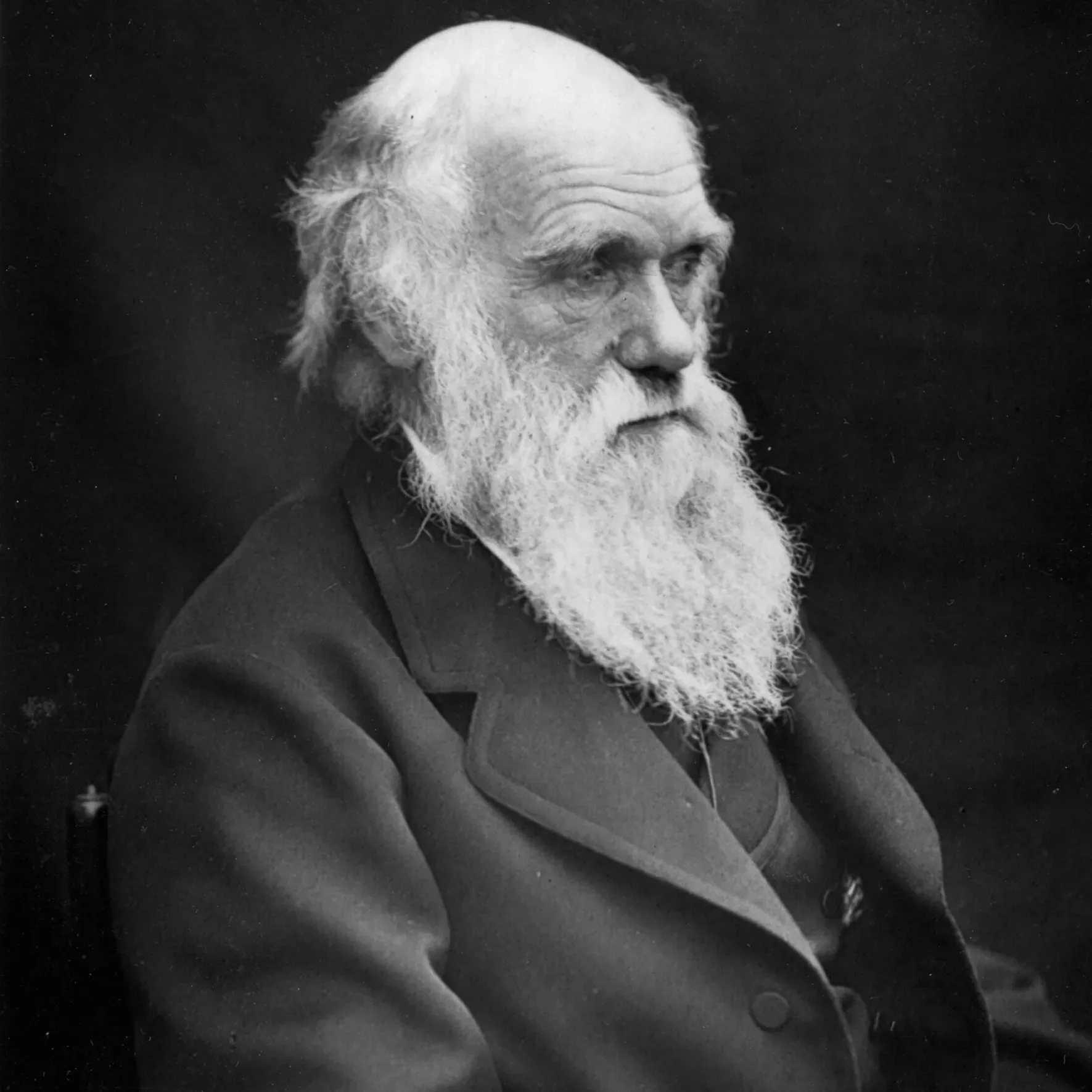

Solving Charles Darwin’s puzzles

In an 1879 letter to Joseph Dalton Hooker, his close confidant and at the time Director of RBG Kew, Darwin wrote

“The rapid development as far as we can judge of all the higher plants within recent geological times is an abominable mystery.”

From analysing the fossil record, Darwin was completely baffled by the rapid rise to dominance of flowering plants, a curiosity that he never had the chance to investigate in full. They account for ~90% of all known plant species today.

Incorporating more than 200 plant fossils into our new tree of life allowed us to explore the diversification of species as they arose across time. While most flowering plant lineages arose in the first boom period after the appearance of the first flowering plants over 140 million years ago, new evidence points to slower, and more stable rates of new species appearance for the next 100 million years, until a second surge in diversification took place around 40 million years before the present day.

This second flowering plant diversification likely coincided with a global decline in temperatures. These insights would have fascinated Darwin were he alive today, but in his place this information produced by the Tree of Life Initiative at Kew will feed countless studies by today’s scientists aiming to understand exactly how and why species diversify.

Tomorrow’s solutions today

Studying the tree of life is not just about looking into the past, but also the future.

Compare this tree of life to the periodic table of elements. Generally, you can point to an area of the periodic table and have a good idea of the properties of any element based on its location – for example, whether it’s solid or liquid at room temperature, or radioactive versus stable.

The tree of life works similarly. We can predict properties of certain plants based on what we understand about their most closely related species.

The potential in this is enormous. Imagine for example being able to explore for chemical compounds with potential use as medicines, based on those we’ve discovered so far.

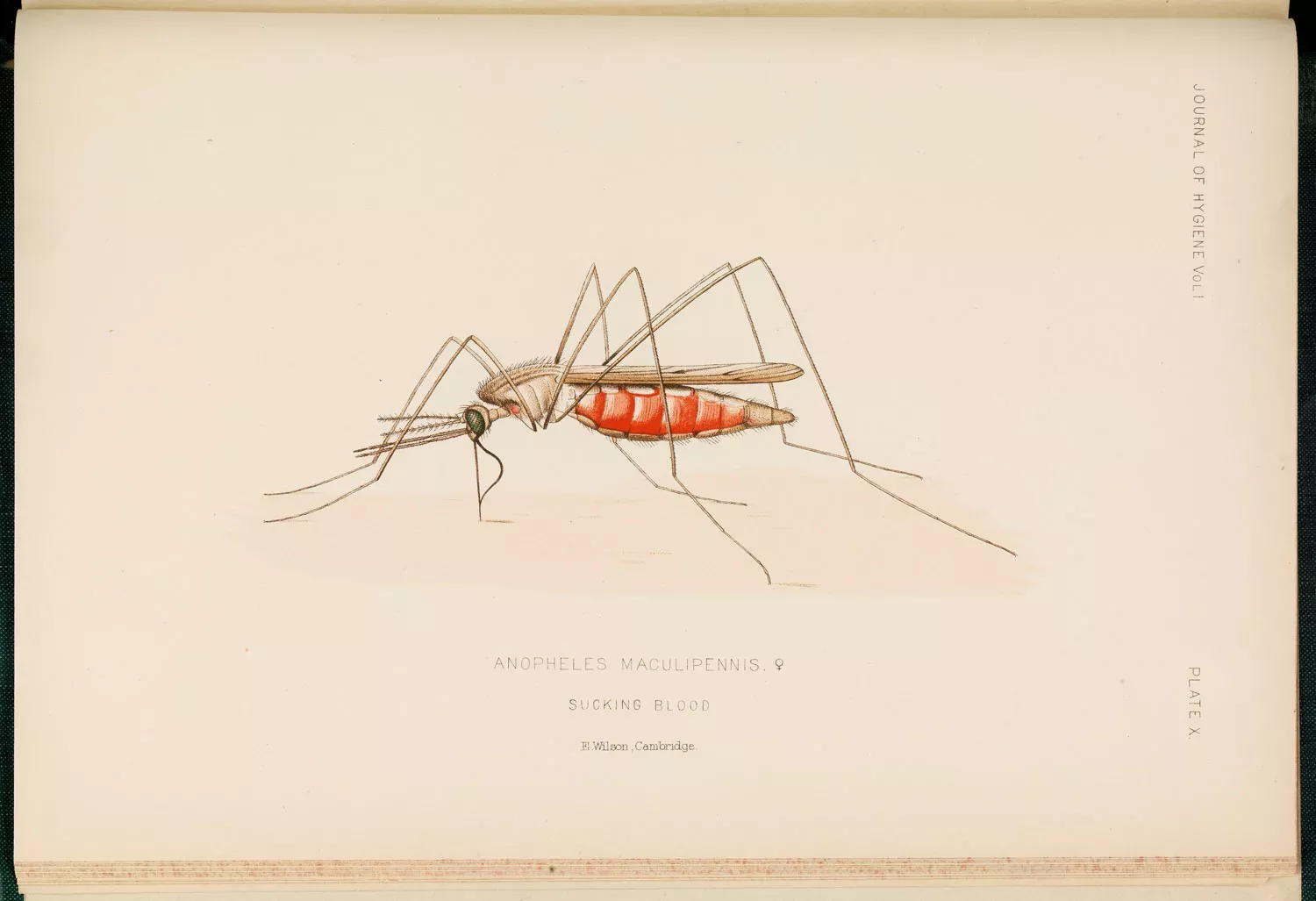

A Kew project is already doing exactly this, utilising artificial intelligence in concert with the tree of life and chemical information to search for plants that might help us create new treatments for malaria – research that will be accelerated with new tree of life information.

We can also make more accurate predictions about how groups of plants are likely to fare under climate change, or how they might deal with certain plant diseases or pests, both of which are pressing questions that are getting hotter alongside our planet.

The Kew Tree of Life Explorer: for you, for all

This new tree of life is invaluable, but the impact it’ll have for our planet will only come from the people of all walks of life from around the world that make use of it.

That’s why together, the creators of the incredible dataset that underpins the Plant tree of life are making it free to use by all, via the Kew Tree of Life Explorer.

Whether it’s solving puzzles of the distant past or preparing for the world around the corner – we can’t wait to see what mysteries the plant tree of life will be used to solve next. What will you use it for?

Find out more about the plant tree of life

Completing the Plant Tree of Life