8 July 2024

The Damselfly and the Fire Bell – Tales from the Kew herbarium

From historic alarms to ancient insects, we’ve come across some unique and unusual things in one of the world’s largest dried plant collections

Kew’s herbarium collection is one of the largest and most referenced international dried plant collections in the world. It acts as a giant archive of plant diversity, containing the rich history of plant scientific names and the people that collected these specimens over more than 200 years!

We two University College London MA Museum Studies students have just completed our placement projects among this collection, under the supervision of Kew's Africa Curation Team. Our experience in this setting has allowed us to develop practical, work-orientated skills.

Kew Herbarium has botanical material constantly coming in as new acquisitions, and going out as loans for research. The aim of our placements was to delve into unprocessed bundles and boxes of plant specimens and prepare the material ready to become a part of the main collections.

The material was full of surprises and puzzles, including frequently unidentified and sometimes historic collections that had either been donated or loaned to Kew. Our focus was on African palm specimens and other miscellaneous bundled plant material. These are our experiences and the unexpected discoveries we made along the way.

A gold mine of plants – understanding the importance of the Herbarium

Among the backlog of material were loans and donations to Kew, sometimes having been stored in other collections for many decades. By donating botanical specimens to a publicly accessible herbarium such as Kew, the material becomes freely available for study both physically and electronically through digitisation.

Before specimens can be incorporated into the herbarium, they are deep-frozen to eradicate pests. They then await attention from specialist taxonomists to verify the plant name before being mounted, imaged, digitised and finally incorporated into the collections for research and safe-keeping.

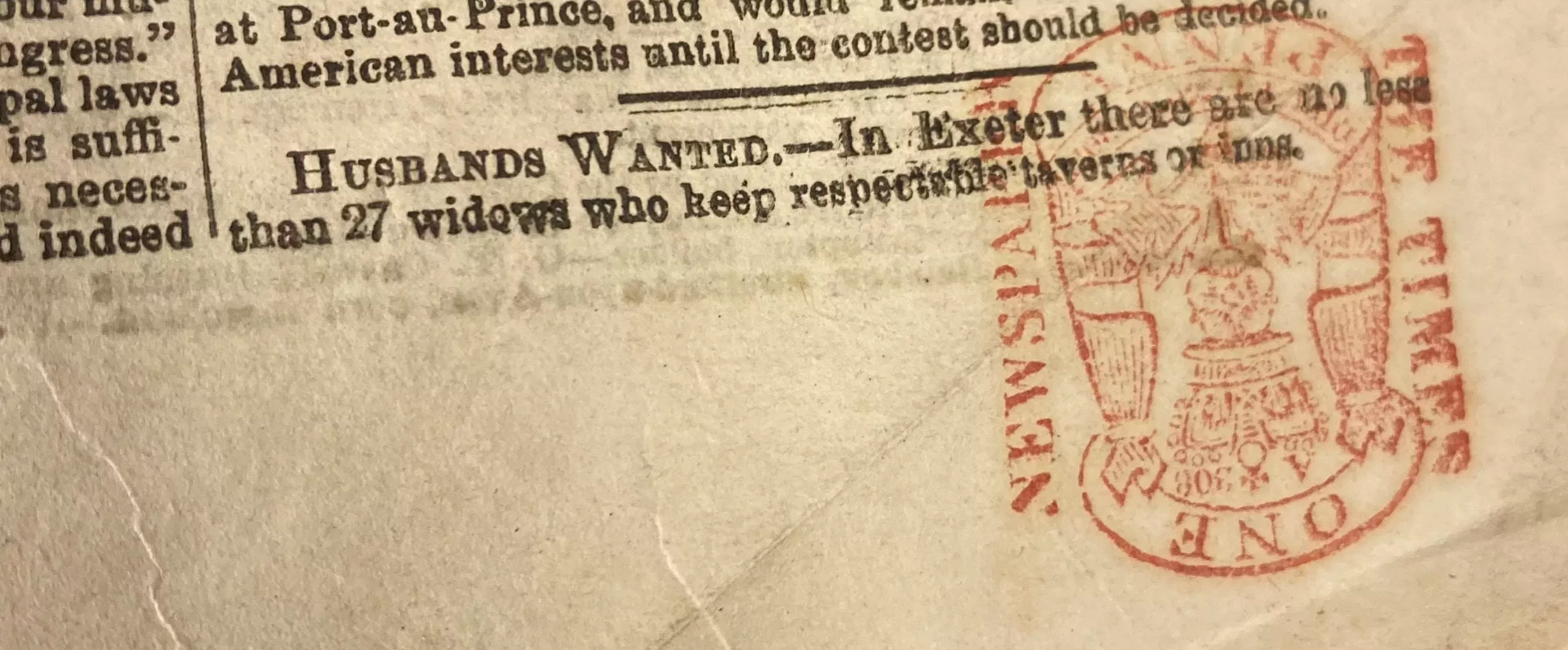

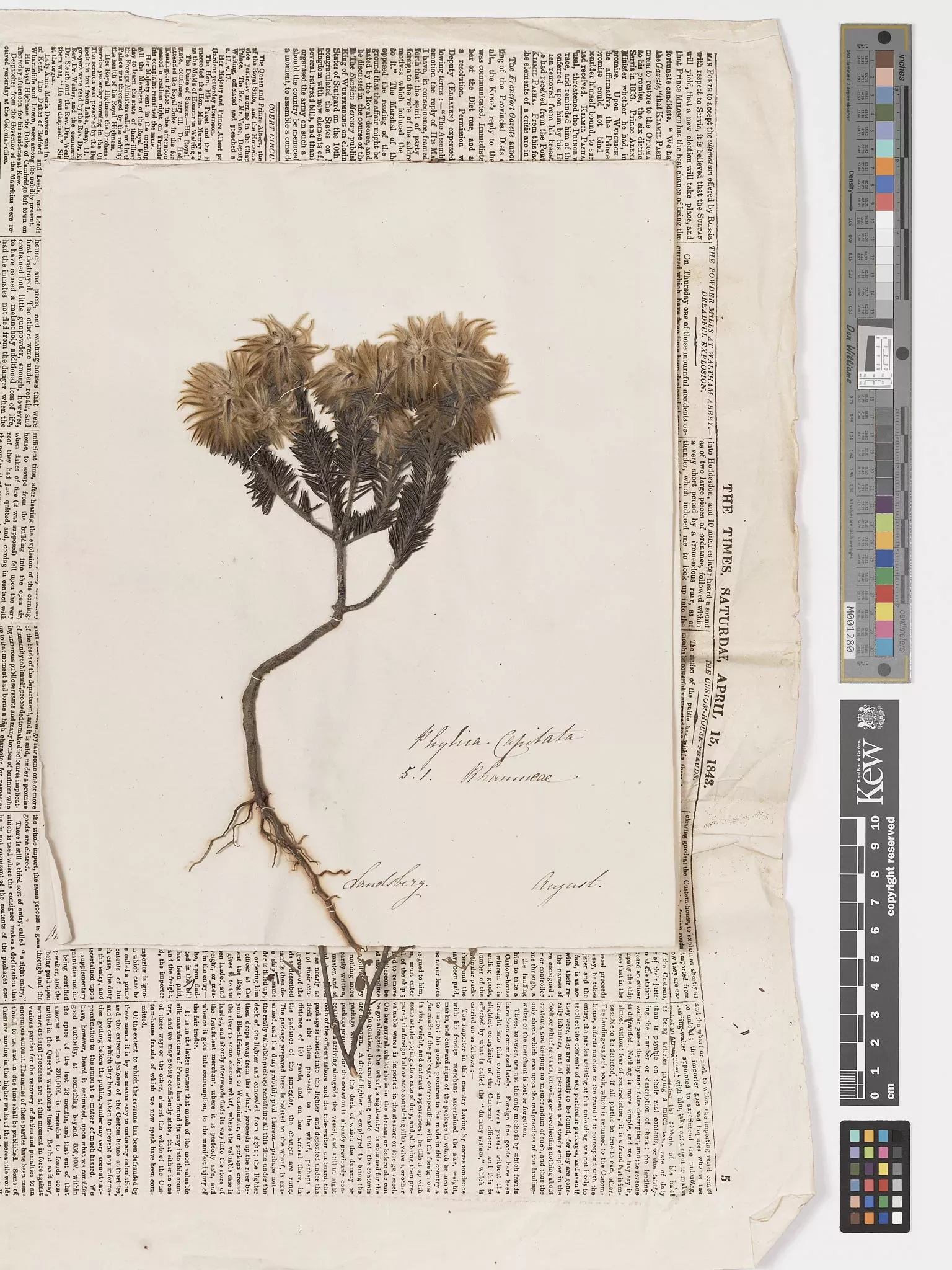

When specimens arrive at Kew Herbarium they are usually wrapped in newspaper from the country in which they were collected. These papers were used to dry specimens in the field and can provide revealing information from that place and time. An example is this short feature (pictured below) from the 1800s – a bit like an early day Tinder where widows in Exeter advertise for husbands.

Every herbarium specimen has a story to tell

Usually, specimens are named in the field when they are cut from a live plant and collected. A collector’s label, which includes the provisional name and contextual information about the specimen, enters Kew together with the dried plant cutting.

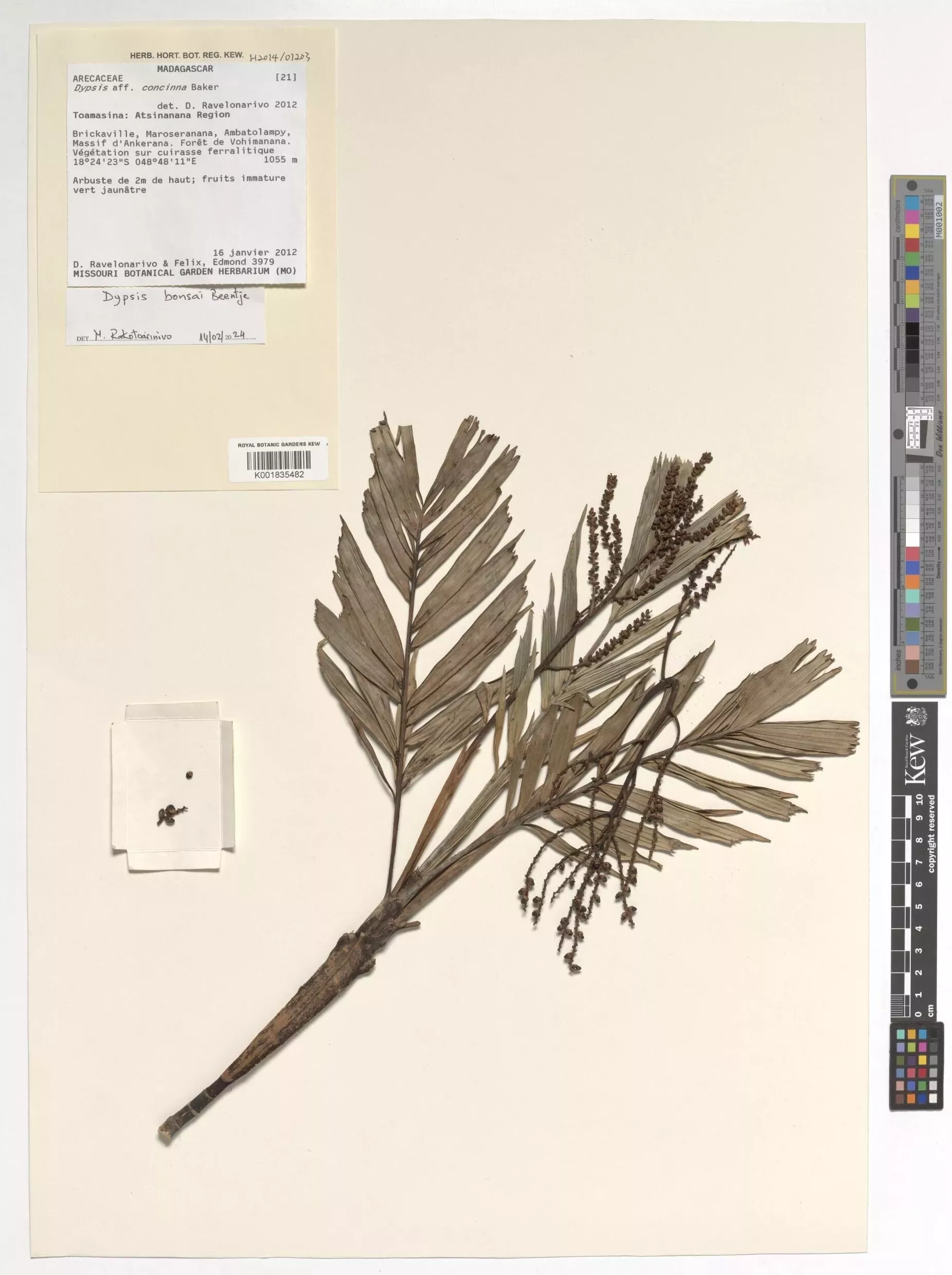

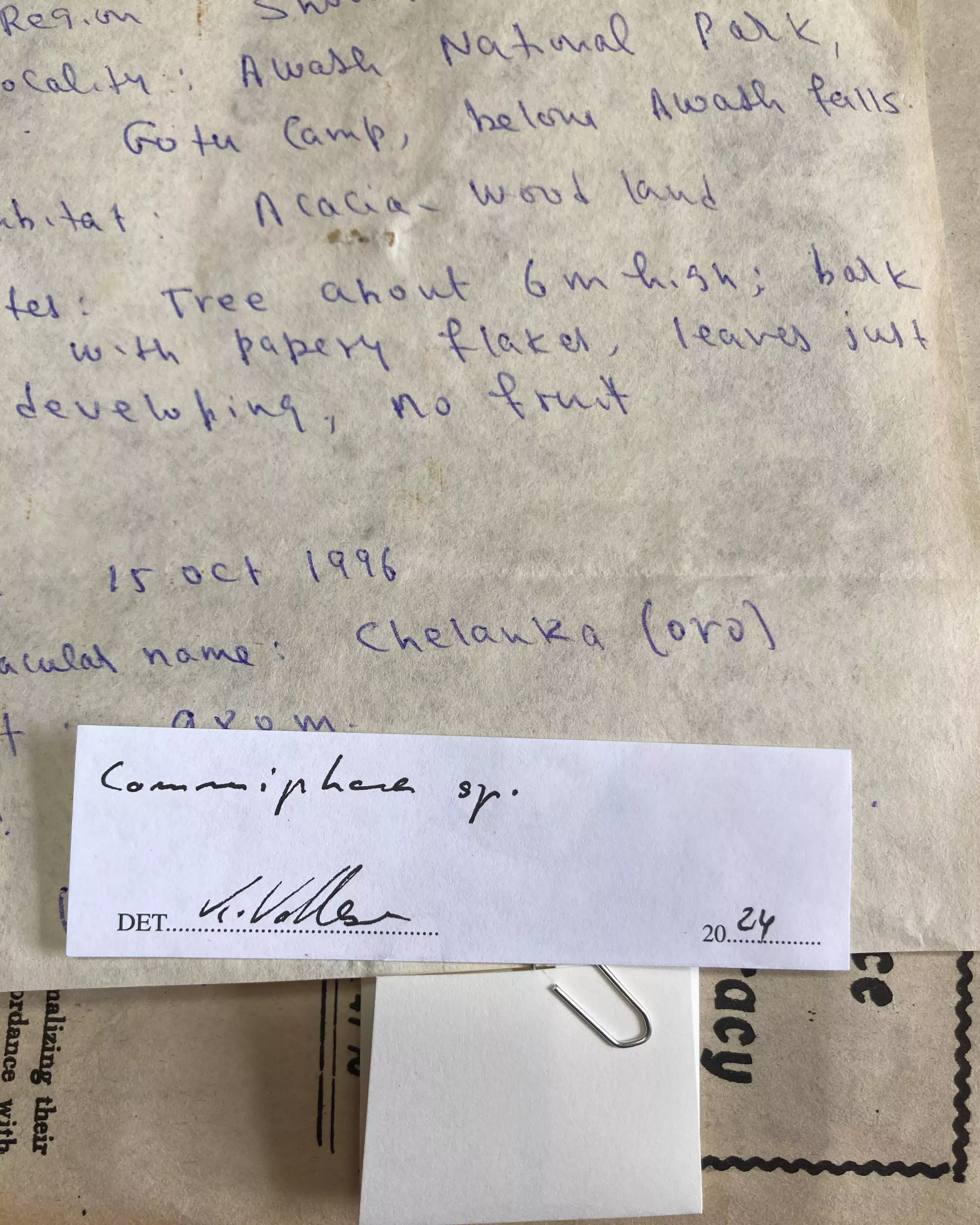

The naming in the field needs to be confirmed using a published key and description, and most importantly, by matching to verified specimens in the collections. During the naming process, botanists at Kew check the specimens and determine, confirm or redetermine their names, writing the identified name on a small, standardised piece of paper called a ‘determination slip’, or ‘det slip’ for short.

Previous det slips are not replaced but added to, allowing us to track each specimen’s story of botanical identification.

The palm specimen pictured below was named as Dypsis aff. concinna by its collector in 2012. The ‘aff.’ is abbreviated Latin for ‘has affinity with’, and means our collector thought it very similar to the species Dypsis concinna, but different enough in some ways that it was not confirmed as this. During the naming process at Kew, it was identified as a different species, Dypsis bonsai, and a new det slip was added to its Kew label.

Plant detective work

Not all specimens arrive with sufficient information to easily allow Kew botanists to identify their species name.

On occasion, specimens arrive with sparse or missing collector data. Some cross-referencing must therefore be done to understand the context of the specimen’s collection.

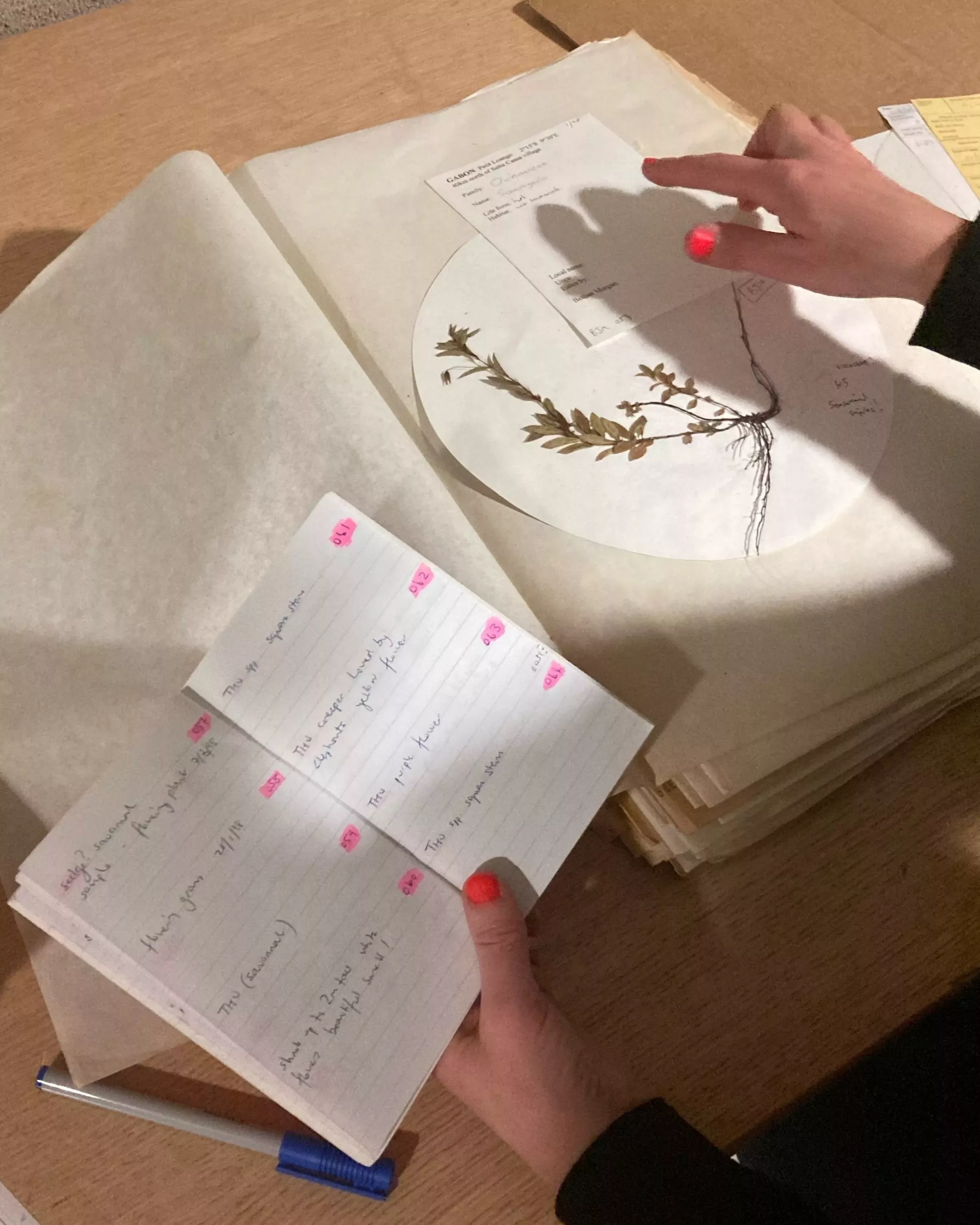

A handful of specimens sourced from Gabon in the 1990s, for example, required a little additional detective work to gather all the information about each specimen.

We cross-referenced each specimen’s unique collector number with the carefully kept notes that the field collector had compiled in a pocket-sized red notebook, as well as the collector’s activity on herbaria databases.

With this extra knowledge we were able to confirm the field data and successfully identify each specimen before its addition to the Kew collection.

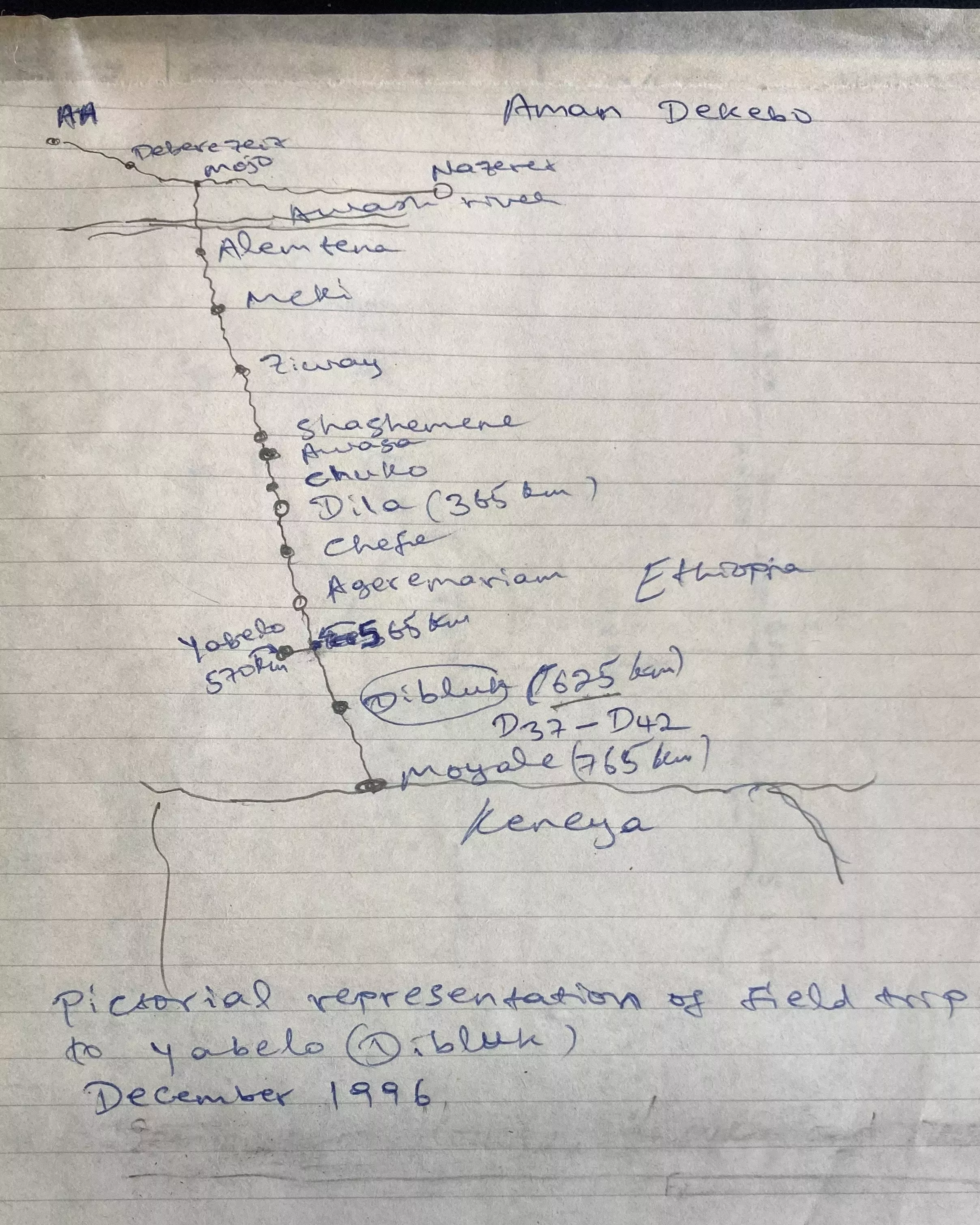

A different collection of specimens from Ethiopia was accompanied by hand-drawn field maps, showing in detail the collection location. By reviewing this additional information, either alongside or in lieu of specimen labels, the name of each specimen could be confirmed by a specialist taxonomist, and a det slip at Kew could be created.

These case studies highlight the importance of field collection information to the herbarium’s work.

The Beautiful Demoiselle

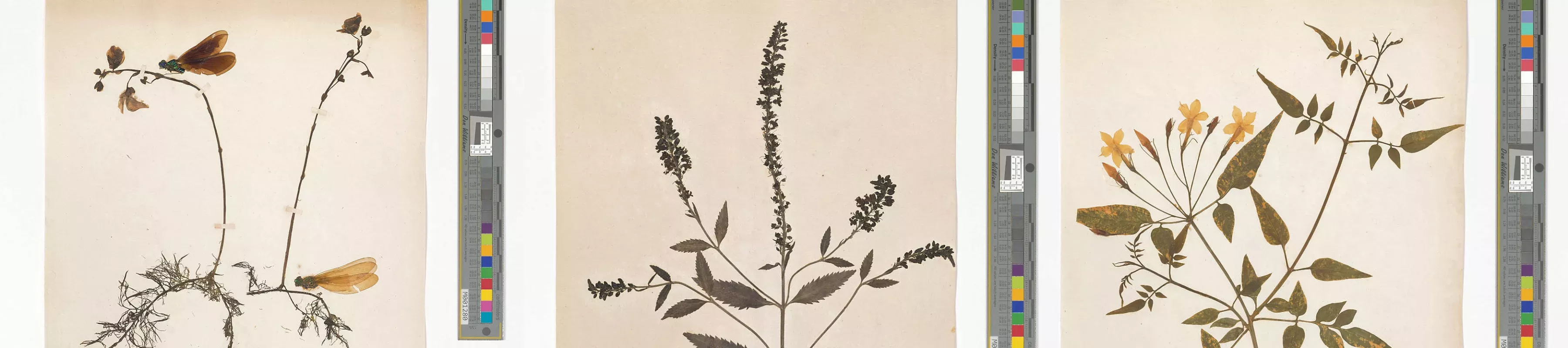

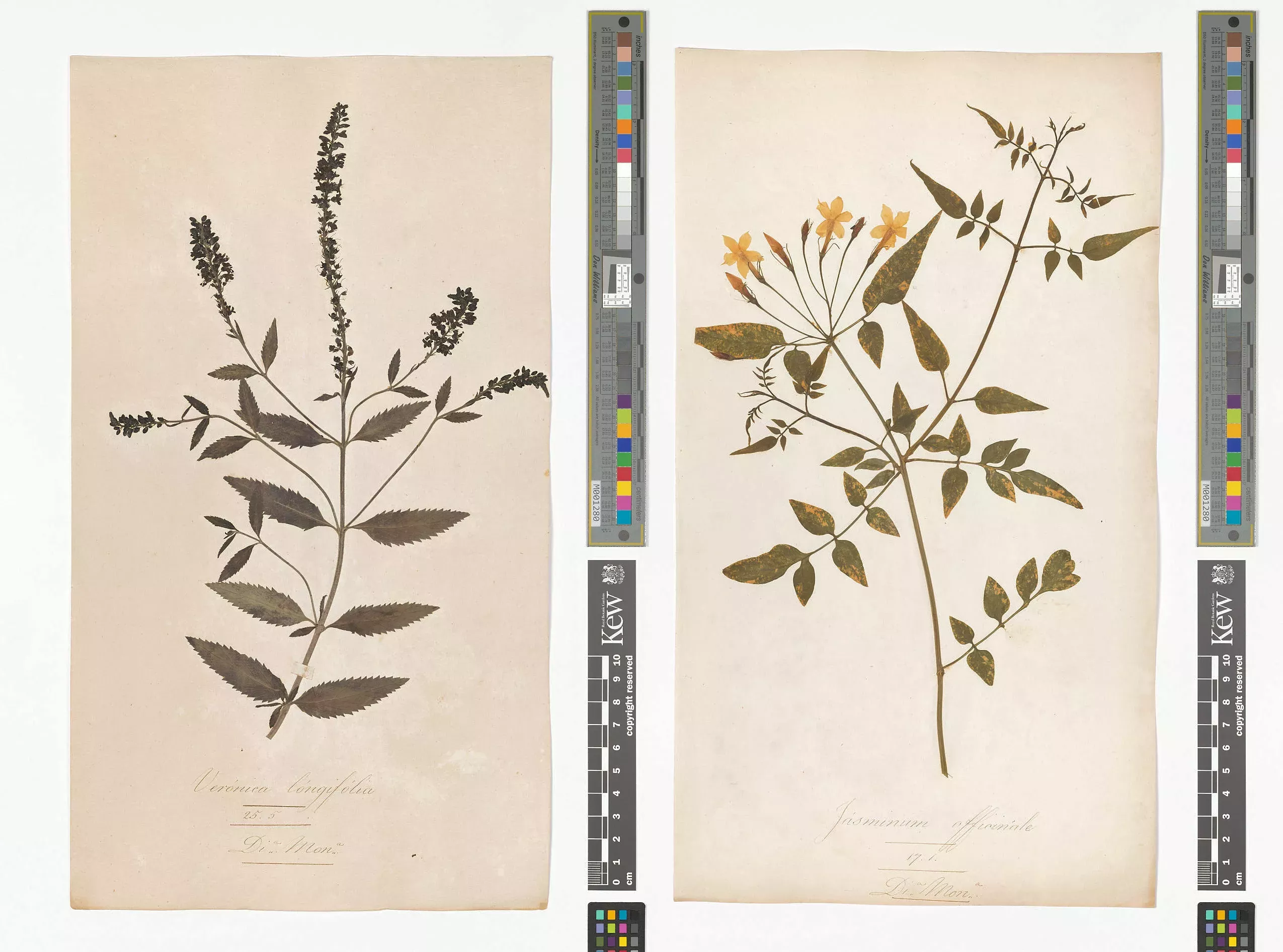

For far older specimens, such as these donated specimens from Bertoloni’s 1833-1857 Flora Italia, there is no standard collector label, but there is some information on the sheet, such as the Linnaean scientific name.

Though these specimens are not African, they were discovered in the Africa backlog and so investigated by the team. Labels made by curation staff for these historic specimens, will mean they can be added to the collection and subsequently digitised, making them open access to all.

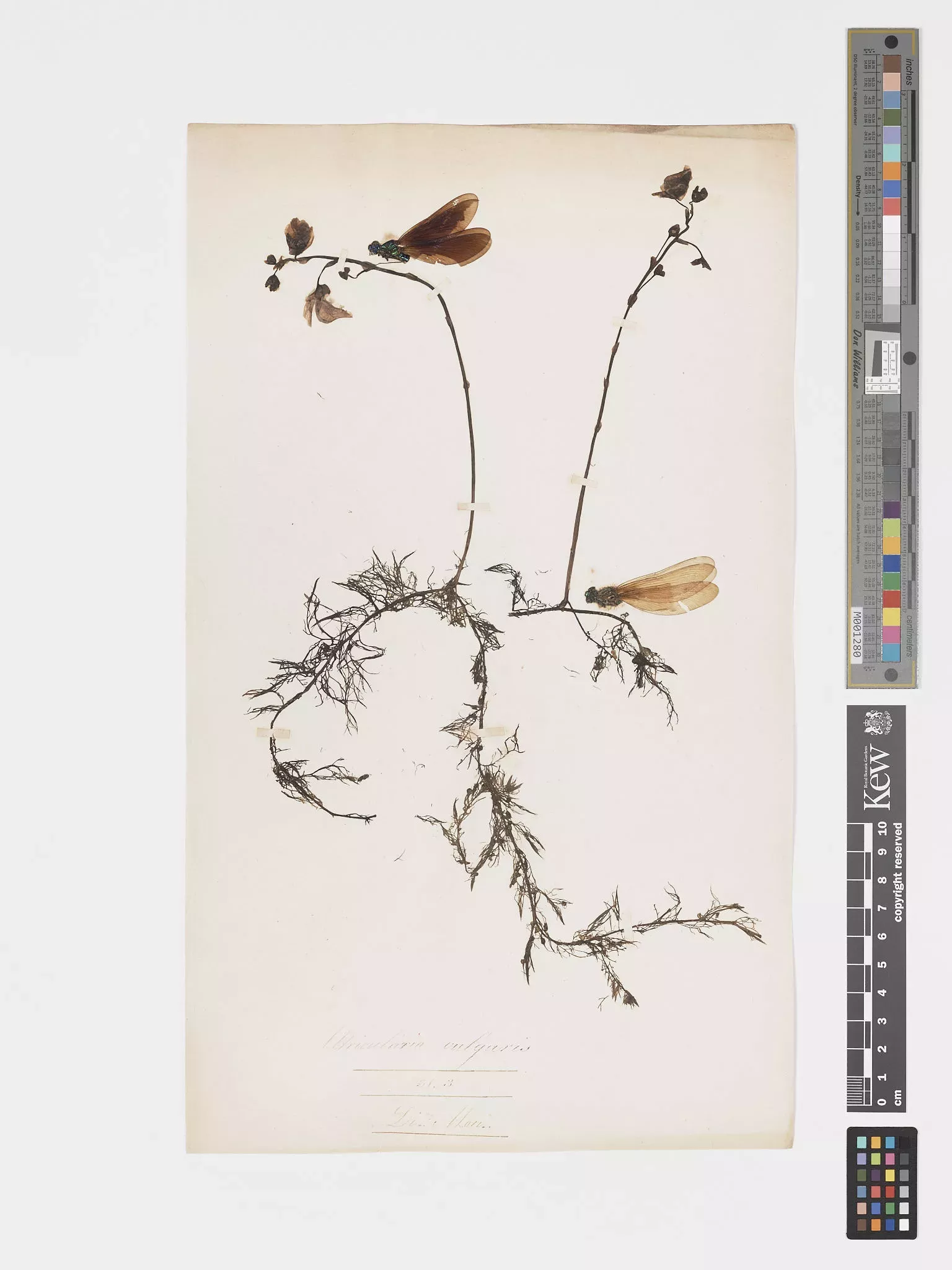

One specimen from this collection was mounted alongside insects - quite unusual for an herbarium specimen.

Principal Curator of Insects at the Natural History Museum, Dr Gavin Broad, has an interest in insects found on herbaria specimens. He identified them as male and female Calopteryx virgo – the Beautiful Demoiselle damselfly, a species that’s still widely distributed across Europe. Its identification offers insight into Bertoloni as a collector.

Historic records from Cape Peninsula

We found an interesting bundle of several hundred specimens loaned for verification by Kew taxonomic specialists. The plants were collected by Rachel Jameson of South Africa in 1841 and are mostly native to the Cape Peninsula, a region of exceptional floristic diversity. In many cases, these dried plants are evidence of their species’ former presence in areas now lost to habitat transformation and the growth of the city of Cape Town.

Fire Safety

Our most unusual find in the herbarium was this old-fashioned fire alarm bell made by Perry Barr Metal. It was discovered forgotten among old equipment used for care of the collection in the Herbarium's oldest wing. It is manually operated and in full, pristine working order - the crank must be turned to trigger the bell sound.

Fire safety has long been of the utmost importance to the care of Kew’s Herbarium collection, though this backup piece from a bygone time, never needed to see service.

Fascinating finds among an invaluable resource

Herbarium specimens and the data that comes with them are a vital resource in the understanding of the world’s flora.

An incredibly important part of Kew Herbarium’s usage is the accurate naming and organisation of its more than 7.5 million specimens. This allows for each and every specimen to be available for study.

The detective work we’ve played a role in is key to combining dried plants, collector notes and digital resources into an organised system that can be used by everyone, everywhere.

Through our placements at Kew Herbarium, we have applied the theoretical knowledge gained from our Museum Studies course to real curatorial practice, alongside the support of our supervisors, Clare Drinkell and Saba Rokni.

This has not only brought us an integral understanding of the curatorial work which goes on at Kew Herbarium, but also a deep appreciation of the herbarium’s contributions to plant science.

%20(1).jpgc07b.webp)

.pngb8de.webp)